U.S. Experienced Steepest Two-year Decline in Life Expectancy in a Century

Social Factors and Health Inequities Are Strongly Associated with Life Expectancy Disparities

September 22, 2022

A young Black male born last year in the United States has a shorter life expectancy than a boy born in Rwanda, a country in which the typical person lives on less than $2 a day. Native Americans born last year could, absent any progress in mortality rates, expect to live roughly as long as people in low-income Sub-Saharan African countries that are some of the poorest in the world.

These and other disturbing findings are drawn from new provisional data on life expectancy in the United States, released in August 2022 by the National Center for Health Statistics, a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC estimates that in 2021, life expectancy at birth—a measure of the average number of years a newborn can expect to live—was 76.1 years, down from 77 years in 2020 and 78.8 years in 2019—the steepest two-year fall in a century. This was the second time in a decade that there has been a sustained downturn in U.S. life expectancy, something that hadn’t happened since World War II.

________________________________________________________________________________

Interpreting life-expectancy data. Estimates of life expectancy are sometimes misunderstood as a fixed prediction for how many additional years the average person will live. Rather, it is a profile of how much longer the average person would live at each age, based on mortality rates from that year. The life expectancies of children born in 2021, for example, can increase in the years ahead if broad-based improvements in health and well-being bring about reduced mortality rates.

________________________________________________________________________________

Pandemic drives life expectancy losses

COVID-19 was the primary driver of the decline in life expectancy since 2019, accounting for about half of the drop in 2021, followed by unintentional injuries (e.g., drug overdoses, motor vehicle accidents, falls, etc.), heart disease, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, and suicide. The effects from these were offset partially by decreases in mortality due to influenza and pneumonia—perhaps connected to masking, social distancing, and other COVID-19-related mitigation actions—as well as chronic lower respiratory diseases, and Alzheimer’s disease, among other causes. Overall, the leading causes of death in the U.S. since the pandemic began have been heart disease, cancer, and COVID-19.

Disparities in life expectancy

Behind these topline numbers is a great deal of variation by sex, race/ethnicity, and income. For example, the difference in life expectancy at birth between the sexes widened in 2020 and again in 2021, reaching 5.9 years in 2021 (Females: 79.1; Males: 73.2), the broadest gap since 1996. Deaths owed to homicide are one reason for this; by age 50, the gap in life expectancy shrinks to 3.9 years.

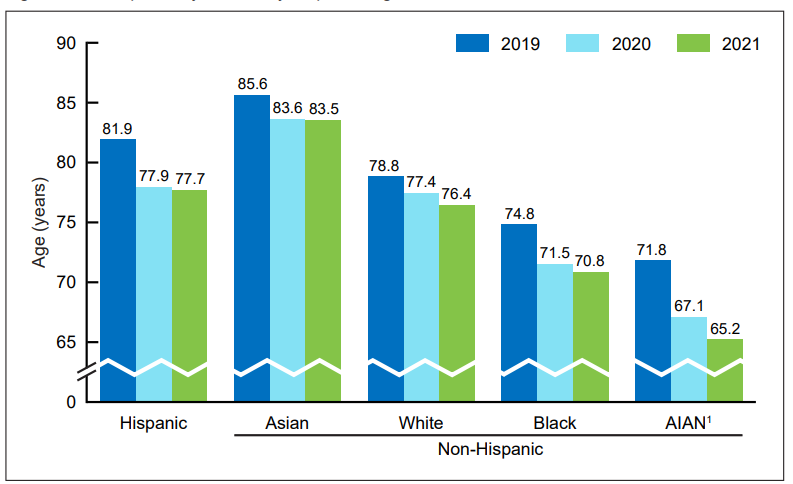

Looking across races and ethnicities, the American Indian or Alaska Native population experienced a devastating loss in life expectancy between 2019 and 2021, from 71.8 years in 2019 to 65.2 years in 2021, a 9 percent decline. Newborns in this population can now be expected to live, on average, as long as the typical U.S. resident in 1944, about the time that penicillin was beginning to be mass produced and two decades before the U.S. Surgeon General’s landmark smoking report. The next greatest declines over the two-year period occurred among Black and Hispanic residents (each 5 percent). Asian men were the only group to experience an increase in life expectancy in 2021; notably, across all races and ethnicities in the U.S. for which data are available, Asian people have the highest COVID-19 vaccination rate.

Entering the pandemic, Native American and Black people experienced higher rates of obesity, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and chronic liver disease than White people, and they developed these chronic conditions earlier in life, putting them at higher risk of mortality from COVID-19 and other leading causes of death. These disparities reflect centuries of marginalization and environmental, economic, medical, and political factors—commonly described as social determinants of health—that contribute to people’s health outcomes.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Life expectancy has also been found to very dramatically by income. For instance, a 2016 study by economist Raj Chetty and others found that the difference for 40-year-olds in the top 1 percent of U.S. income distribution and in the bottom 1 percent was 15 years for men and 10 years for women, and this chasm had widened over time. Interestingly, there was even significant regional variation among people with low incomes, reflecting individual differences (e.g., obesity, smoking, exercise) as well as local levels of education and government expenditures.

One way to see this impact in the data is to compare the life expectancies of various states. For example, in 2020, life expectancies at birth of residents in Maryland (76.8 years), New Hampshire (79 years), and Massachusetts (79 years), the states with the highest median household incomes (excluding the District of Columbia), were much higher than in Mississippi (71.9 years), Arkansas (73.8 years), and New Mexico (74.5 years), the states with the lowest median household incomes.

Divergences can be starker at the local level. For example, even before the pandemic, a team of researchers at New York University found that, among the 500 largest cities in the U.S., 56 had life expectancy gaps between neighborhoods separated by just a few miles of up to 20 to 30 years. The largest gaps tended to be in cities with higher levels of racial and ethnic segregation. In New York City, for example, people living in East Harlem lived, on average, 19 years less than residents of the Upper East Side, which is just a few blocks away.

________________________________________________________________________________

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman.” Martin Luther King, Jr.

________________________________________________________________________________

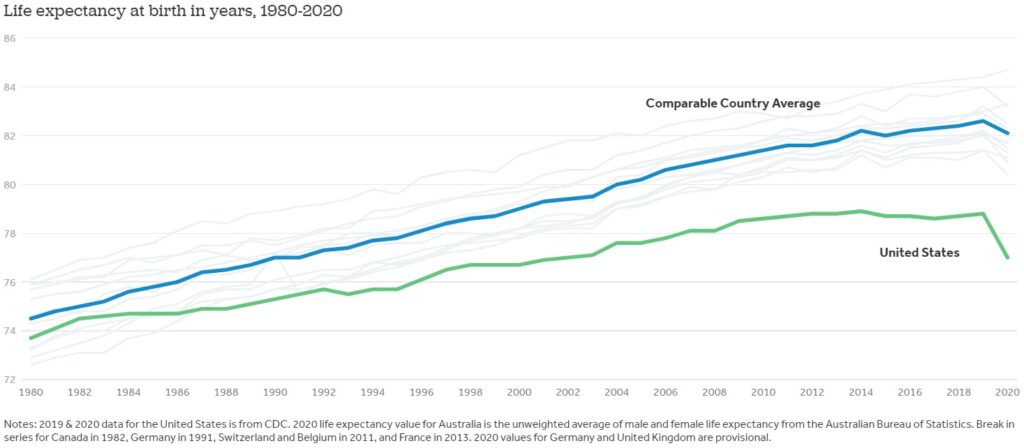

The national trend in the U.S. over the past few decades are especially disturbing when compared to peer countries. Indeed, researchers at the Peterson Center on Healthcare and the Kaiser Family Foundation have demonstrated how, since the 1980s, growth in life expectancy at birth in the U.S. has separated from that of comparable countries. And whereas life expectancy fell in 2021 for the second consecutive year, it rebounded in most peer countries, resulting in an estimated 1.1 million “missing Americans” (i.e., people who would still be alive if U.S. mortality rates had matched the average of the comparison group) from that year alone, equating to 25 million lost years of life. Setting deaths from COVID-19 aside, the leading contributors to the U.S.’s outlier status are its high rates of deaths tied to obesity, overdoses, gun deaths (including homicides and suicides), and traffic fatalities.

Source: Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

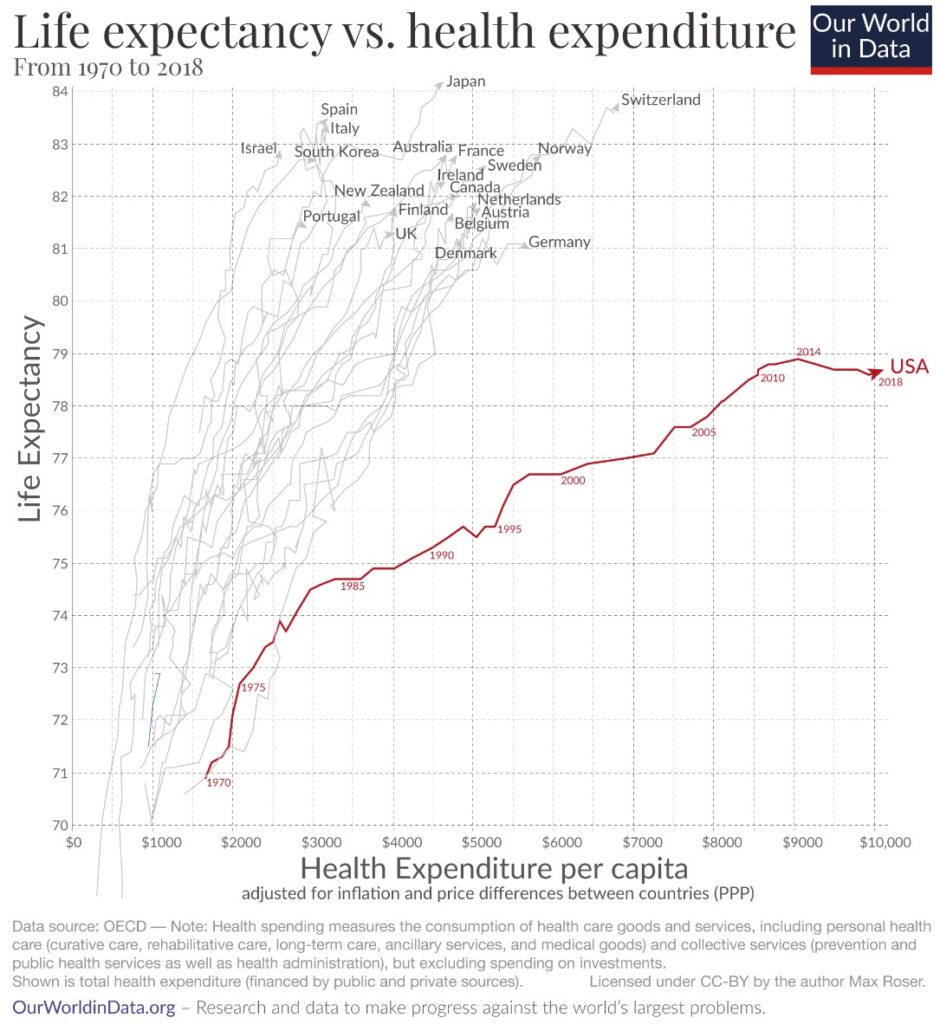

It might be tempting for some to review all of these statistics and come away thinking that the solutions can be arrived at through greater levels of healthcare spending, but the available evidence suggests that’s not the case. Indeed, the United States spends far more on healthcare on a per capita basis but, tragically, achieves much poorer results. That suggests that the most effective solutions are to be found in preventing disease and injury and promoting health—the central aims of public health.

Source: Our World in Data

Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) serves this mission by working to promote optimal health for every person and community and making the prevention of illness and injury a national priority. We report on and recommend evidence-based programs and policies that make prevention and health equity foundational to health and community systems at all levels of society. Our goal is a modernized, public health system that meets the challenge of health equity for all and is prepared to respond to a wide variety of health threats in an inclusive, community appropriate, and rigorous manner. These efforts, and indeed TFAH’s strategic focus on some of the country’s greatest challenges, are reflected in our work on obesity; deaths from alcohol, drugs, and suicide; public health emergency preparedness; and health equity, among other areas.

With deaths from COVID-19 on track to be lower in 2022 than in 2021, there is reason to hope for a reversal in life expectancy trends from the past two years. But there’s much work to be done to protect U.S. residents from COVID-19 and address persistent long-term issues that preceded the pandemic. TFAH looks forward to working with fellow researchers and advocates, communities, and their policymakers to bring about much-needed, broad-based progress.