State Category: Rhode Island

When Two Health Risks Merge – Rising Obesity Rates Put More Americans at Risk for Serious Health Impacts of the Novel Coronavirus

High obesity rates in communities of color may be one of a number of factors leading to severe COVID-19 impacts in those communities

(Washington, DC – May 6, 2020) – New data drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that 42.4 percent of U.S. adults age 20 and older have obesity. That rate was up nearly three percentage points from the previous NHANES survey taken in 2015-2016 when 39.6 percent of the nation’s adults had obesity. After remaining relatively stable in the 2000s, these new data represent the third consecutive NHANES survey that found increases in the nation’s adult obesity rate of 2.8, 1.9 and 2.8 percentage points respectively.

The latest survey also showed a continuing pattern of higher rates of obesity in Black and Latino communities than in the White population. Among adults, the prevalence of both obesity and severe obesity was highest in Black adults compared with other races/ethnicities.

Rates of Obesity – U.S. Adults by Race:

- Blacks – 49.6%

- Latinos – 44.8%

- Whites – 42.2%

Rates of Obesity – U.S. Adults by Race and Gender

- Black Women – 56.9%

- Black Men – 41.1%

- Latina Women – 43.7%

- Latino Men – 45.7%

- White Women – 39.8 %

- White Men – 44.7 %

Childhood obesity is also increasing across the country. Having obesity as a child puts you at a higher risk of having obesity as an adult.

Having obesity puts people at higher risk for severe COVID-19 impact

It is well-established that obesity is associated with serious health risks. The risk of diabetes is closely associated with obesity. In addition, people with obesity have higher levels of pre-existing respiratory and cardiac disease which puts them at higher risk for serious impacts if infected by the novel coronavirus. In a study in review for publication, researchers at New York University found that obesity is one of three of the most common risk factors for COVID-19 hospitalizations.

The COVID-19 crisis is disproportionately causing severe illness and taking the lives of Black Americans. As of April, of COVID-19 positive tests where the patient’s race/ethnicity was known, 28.5 percent were Black. Blacks make-up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population. Additional examples include Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Blacks are 28 percent of the county’s population but as of early April were 73 percent of its coronavirus deaths. In Michigan, Blacks are 14 percent of the state’s population and 41 percent of the state’s coronavirus deaths. In Chicago, Blacks are 23 percent of the city’s residents and 58 percent of its coronavirus deaths.

The social, economic, and environmental conditions that lead to higher rates of obesity and other chronic diseases in communities of color are tied to factors that also elevate the risk of COVID-19 related hospitalizations and death. Factors such as lack of economic opportunities, for example in the form of good jobs with living wages, contribute to obesity by making it more difficult to afford healthier foods or have access to stores that sell affordable healthy produce. Additional conditions in many communities of color that contribute COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths are living in multigenerational households, working in public-facing jobs that elevate COVID-19 risk (such as work in home health care, grocery stores, delivery services and the public transit system) and less access to healthcare.

“Numerous factors are leading to the tragic overrepresentation of people of color in the nation’s COVID-19 deaths, among them the number of people of color working on the frontlines as essential workers, where telework or physical distancing is not possible,” said Dr. J. Nadine Gracia, Trust for America’s Health’s Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer. “In addition, high levels of chronic disease within communities of color, such as diabetes and heart disease, are contributing to higher levels of COVID-19 deaths”.

The nation’s obesity crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to interact in additional ways. For example, food insecurity is associated with obesity. An additional contributing factor is lack of physical activity. Unfortunately, COVID-19 will increase both of those concerns as millions of families are currently food insecure due to job loss and many places to exercise such as gyms, community centers and parks are closed.

“The COVID-19 crisis has illuminated systemic and structural inequities that impact the health and well-being of people of color,” Dr. Gracia said. “The factors associated with maintaining a healthy weight are another example of the ways in which where people live, the neighborhood resources available, and the economic opportunities afforded to them drive their health, and are now driving their degree of health risk due to COVID-19.”

While federal and state leaders are immediately focused on protecting lives during the current crisis, investing in programs to stem the rise in the country’s obesity rates will not only improve Americans’ health, it will also make the country more resilient during future health emergencies.

Some of the federal policy actions TFAH recommends to reverse the country’s rising obesity rates are:

- Congress should fully fund CDC’s Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity’s SPAN (State Physical Activity and Nutrition program) grants for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Current CDC funding only supports 16 states out of 50 approved applications.

- Congress should increase funding for CDC’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program which works with community organizations to deliver effective local and culturally appropriate obesity prevention programs in communities that bear a disproportionate burden of chronic disease. Current funding only supports 31 grantees out of 261 approved applications.

- Build capacity for CDC and public health departments to work with other sectors (such as housing and transportation) to address social determinants of health, the nonmedical factors that affect communities’ health status including rates of obesity.

- Without decreasing access or benefit levels, ensure that anti-hunger and nutrition-assistance programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) follow the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and make access to nutritious food a core program tenet.

- Expand the WIC program to age 6 for children and for two years postpartum for mothers. Fully fund the WIC Breastfeeding Peer Counseling Program.

- Increase the price of sugary drinks through excise taxes and use the revenue to address health and socioeconomic disparities. Increasing the price of surgery drinks has been shown to decrease their consumption.

- Enforce existing laws that direct most health insurers to cover obesity-related preventive services at no-cost sharing to patients. Comprehensive pediatric weight management programs and services should also be covered by Medicaid.

- Encourage safe physical activity by funding Complete Streets, Vision Zero and other pedestrian safety initiatives through federal transportation and infrastructure funding.

- In schools, strengthen and expand school nutrition programs beyond federal standards to include universal meals and flexible breakfasts, eliminate all unhealthy food marketing to students, support physical education programs in all schools and expand programs that ensure students can safely walk or ride bicycles to and from school.

See TFAH’s State of Obesity: Better Policies for a Healthier America 2019 for additional recommendations on how to stem the country’s obesity crisis. https://www.tfah.org/report-details/stateofobesity20

The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2020

New Report Shows Hamstrung COVID-19 Response was Years in the Making

Funding for public health preparedness and response programs lost ground in FY 2020 and over the past decade.

(Washington, DC – April 16, 2020) – Chronic underfunding of the nation’s public health and emergency preparedness systems has made the nation vulnerable to health security risks, including the novel coronavirus pandemic, according to a new report released today by Trust for America’s Health.

The report, The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2020, examines federal, state, and local public health funding trends and recommends investments and policy actions to build a stronger system, prioritize prevention, and effectively address twenty-first-century health risks.

“COVID-19 has shined a harsh spotlight on the country’s lack of preparedness for dealing with threats to Americans’ well-being,” said John Auerbach, President and CEO of Trust for America’s Health. “Years of cutting funding for public health and emergency preparedness programs has left the nation with a smaller-than-necessary public health workforce, limited testing capacity, an insufficient national stockpile, and archaic disease tracking systems – in summary, twentieth-century tools for dealing with twenty-first-century challenges.”

Mixed Picture for CDC FY 2020 Funding

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the nation’s leading public health agency. The CDC’s overall budget for FY 2020 is $7.92 billion – a $645 million increase, 9 percent over FY 2019 CDC funding, 7 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars. The largest FY 2020 increase was a onetime investment in buildings and facilities (+$225 million). Other increases included funding for the Ending HIV initiative (+$140 million) and small increases for suicide and chronic disease prevention programs.

Emergency Preparedness Funding Down This Year and For Over a Decade

Funding for CDC’s public health preparedness and response programs decreased between the FY 2019 and FY 2020 budgets – down from $858 million in FY 2019 to $850 million in FY 2020. CDC’s program funding for emergency preparedness in FY 2020 ($7.92 billion) is less than it was in FY 2011 ($7.99 billion in FY 2020 dollars), after adjusting for inflation.

Funding for state and local public health emergency preparedness and response programs has also been reduced, by approximately one-third since 2003. And, of critical concern now, funding for the Hospital Preparedness Program, the only federal source of funding to help the healthcare delivery system prepare for and respond to emergencies, has been cut by half since 2003.

Federal action to enact three supplemental funding packages to support the COVID-19 pandemic response was critical. But they are short-term adjustments that do not strengthen the core, long-term capacity of the public health system, according to the report’s authors. Sustained annual funding increases are needed to ensure that our health security systems and public health infrastructure are up to the task of protecting all communities.

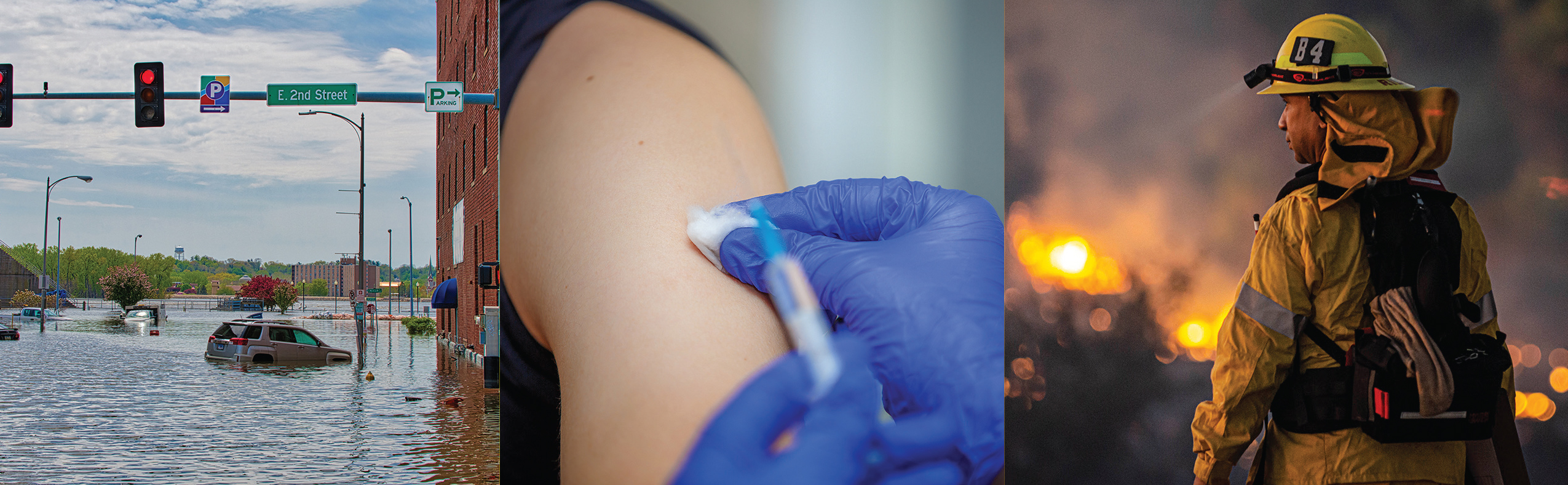

The nation’s habitual neglect of public health, except during emergencies, is a longstanding problem. “Emergencies that threaten Americans’ health and well-being are becoming more frequent and more severe. These include wildfires and flooding, the opioid crisis, the increase in obesity and chronic illness, and this year a measles outbreak, serious lung injuries due to vaping, and the worst pandemic in a century. We must begin making year-in and year-out investments in public health,” Auerbach said.

In addition to supporting federal activities, federal monies are also the primary source of funding for most state and local public health programs. During FY 2018, 55 percent of states’ public health expenditures, on average, were funded from federal sources. Therefore, federal spending cuts have a serious trickle-down effect on state and local programs. Between FY 2016 and FY 2018, state expenditures of federal monies for public health activities decreased from $16.3 billion to $12.8 billion. On top of federal cuts, some states have also reduced public health funding. More than 20 percent of states (eleven) cut their public health funding between 2018 and 2019.

These funding cuts have led to significant workforce reductions in state and local public health departments. In 2017, 51 percent of large local public health departments reported job losses. Some of the positions lost were frontline public health staff who would have been mobilized to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The report includes 28 policy recommendations to improve the country’s emergency preparedness in four priority areas:

- increased funding to strengthen the public health infrastructure and workforce, including modernizing data systems and surveillance capacities.

- improving emergency preparedness, including preparation for weather-related events and infectious disease outbreaks.

- safeguarding and improving Americans’ health by investing in chronic disease prevention and the prevention of substance misuse and suicide.

- addressing the social determinants of health and advancing health equity.

The report also endorses the call by more than 100 public health organizations for Congress to increase CDC’s budget by 22 percent by FY 2022.

# # #

Trust for America’s Health is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes optimal health for every person and community and makes the prevention of illness and injury a national priority. Twitter: @healthyamerica1

Cross-Sector Group of Eighty-eight Organizations Calls on Congress to Address Americans’ Mental Health and Substance Misuse Treatment Needs as Part of COVID-19 Response

Nation must prepare for immediate and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on the nation’s mental health

(Washington, DC – March 20, 2020) — A cross-sector group of 88 organizations from the mental health and substance misuse, public health and patient-advocacy sectors are jointly calling on the Trump Administration and Congress to address the immediate and long term mental health and substance misuse treatment needs of all Americans as part of their COVID-19 response. Such consideration is especially important as the anxiety and social isolation related to the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the need for mental health and substance misuse care, according to the group’s leaders.

In a letter sent to Vice President Pence and House and Senate leadership today, the group recognizes the importance of social distancing but also cites the need to proactively address the short and long-term impacts of social isolation on Americans’ mental health. Of particular concern are those people who are currently being treated for a mental health or substance misuse issue, treatment that may be interrupted by illness, stay-at-home orders, business shut-downs or the loss of income or health insurance.

Access to mental health and substance misuse treatment is an ongoing concern, likely to be exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. Currently, 112 million Americans live in a mental health professional shortage area. Furthermore, loneliness and social isolation are already a daily reality for many Americans and is estimated to shorten a person’s life by 15 years – the equivalent impact of having obesity or smoking 15 cigarettes a day. This problem will only increase as further social distancing requirements are put in place.

The cross-sector group is calling for immediate action to address Americans’ mental health and substance misuse needs during the COVID-19 response. And, for the longer term, strengthening the nation’s mental health and substance misuse treatment system so it meets the needs of all Americans, regardless of their socioeconomic status, their employment status or where they live.

The group is following for the following action steps: The Administration and/or Congress should:

Immediately implement measures to ensure access and continuation of mental health and substance use services to all individuals during the COVID-19 response and during future public health emergencies including:

- HHS should issue guidance clarifying that mental health and substance use clinicians and professionals are included in priority testing for COVID-19as well as targets of emergency medical supplies including masks, respirators, ventilators, and other needed resources for health care professionals during this crisis.

- CMS should issue guidance for various care contingencies should substance use treatment providers become sick or unable to work and affect required quotas for reimbursement.

- SAMHSA should issue guidance to support remote recovery support groups.

- Congress should pass S. 2244/H.R. 4131, the Improving Access to Remote Behavioral Health Treatment Act, to clarify the eligibility of community mental health and addiction treatment centers to prescribe controlled substances for opioid use disorder via telemedicine. HHS recently waived the Ryan Haight restrictions for this pandemic, but this ends once the national emergency ends which could create treatment gaps.

- HHS should launch a special enrollment period for commercial health insurance in the healthcare.gov marketplace during this crisis and future public health crises.

- Congress should ensure that all government health plans provide extended supplies and/or mail order refills of prescriptions.

- Congress should allow for all current discretionary and block grant funds for mental health and substance use programs, including prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery support, across all relevant agencies across the federal government that cannot be spent this fiscal year due to the pandemic to be automatically extended into Fiscal Year 2021.

Pass, implement, and/or appropriate funding to strengthen crisis services and surveillance including:

- S. 2661/H.R. 4194, the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, which would formally designate a three-digit number for the Lifeline.

- H.R. 4564, The Suicide Prevention Lifeline Improvement Act, which would implement a set of quality metrics to ensure resources are effective and evidence-based.

- H.R. 4585, the Campaign to Prevent Suicide Act, which establishes an educational campaign to advertise the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and suicide prevention resources.

- H.R. 1329, Medicaid Reentry Act, which would allow Medicaid-eligible incarcerated individuals to restart their benefits 30 days pre-release.

- Increase funding for the Disaster Distress Helpline.

- Increase funding to serve people who are homeless and to divert people who are at immediate risk of becoming homeless during this crisis.

Pass and implement reforms to ensure long-term availability of care, especially for populations at higher risk of self-harm or substance misuse, including:

- S. 824/H.R. 1767, the Excellence in Mental Health and Addiction Treatment Expansion Act, which would expand the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Program.

- S. 1122/H.R. 1109, the Mental Health Services for Students Act which expands SAMHSA’s Project AWARE State Educational Agency Grant Program to support the provision of mental health services.

- S. 2492/H.R. 2599, the Suicide Training and Awareness Nationally Delivered for Universal Prevention (STANDUP) Act, which would create and implement suicide prevention training policies in states, tribes, and school districts.

- Enforce mental health parity and pass S. 1737/H.R. 3165, the Mental Health Parity Compliance Act and S. 1576/H.R. 2874, the Behavioral Health Transparency Act.

- Expand HRSA’s NHSC Substance Use Disorder Workforce Loan Repayment Program H.R. 2431, the Mental Health Professionals Workforce Shortage Loan Repayment Act, which would establish a loan repayment program for mental health professionals working in shortage areas.

- S. 2772/H.R. 884, the Medicare Mental Health Access Act, which would allow expanding the definition of “physician” under Medicare, allowing psychologists to practice to the full extent of their state licensure without physician oversight of Medicare facilities.

HHS should consider the mental health and substance use effects of future pandemics and national emergencies including:

- Establishing an interagency taskforce or advisory committee on disaster mental health and substance use to ensure future responses take proper measures to coordinate care, allocate resources, and take appropriate measures to ensure recovery.

- Convening a working group to review current research and funding on disaster mental health through NIH, AHRQ, CDC, SAMHSA, HRSA, FDA, and the Department of Justice, and other relevant agencies and identify gaps in knowledge, areas of recent progress, and necessary priorities.

Signing on to the letter were:

2020 Mom, AAMFT Research & Education Foundation, Active Minds, Addiction Connections Resource, Advocates for Opioid Recovery, African American Health Alliance, American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry, American Art Therapy Association, American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, American Association for Psychoanalysis in Clinical Social Work, American Association of Suicidology, American Counseling Association, American Dance Therapy Association American Foundation for Suicide Prevention American Group Psychotherapy Association, American Mental Health Counselors Association, American Psychological Association, American Public Health Association, Anxiety and Depression Association of America, California Pan-Ethnic Health Network Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)Centerstone, Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Clean Slate Medical Group -Addiction Treatment, Clinical Social Work Association, Coalition to End Social

Isolation & Loneliness, College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP )Colorado Children’s Campaign Columbia Psychiatry, Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA, )Community Care Alliance Davis Direction Foundation, Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Easterseals, Eating Disorders Coalition, Families USA, Flawless Foundation, Foundation for Recovery, Global Alliance for Behavioral Health and Social Justice, Greater Philadelphia Business Coalition on Health, Health Resources in Action, Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, InnovaTel, Telepsychiatry International, OCD Foundation,

Mental Health America, NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals, National Association of County Behavioral Health and Developmental Disability Directors, National Association for Rural Mental Health (NARMH), National Alliance on Mental Illness, National Association for Children of Addiction (NACoA, )National Association of Community Health Workers, National Association of Counties, National Association of Social Workers, National Association of Social Workers -Texas Chapter, National Association of Social Workers at the University of Southern California, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, National Council for Behavioral Health, National Eating Disorders Association, National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health, National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, National Register of Health Service Psychologists, Network of Jewish Human Service Agencies, Neurofeedback Advocacy Project, New Jersey Association of Mental Health and Addiction Agencies, Inc., O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Postpartum Support International, Prevention Institute, Public Health Foundation, Residential Eating Disorders Consortium, Robert Graham Center, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, San Juan County Behavioral Health Department, Sandy Hook Promise SMART Recovery, Staten Island Partnership for Community Wellness, Suicide Awareness Voices of Education, Texans Care for Children, The Confederation of Independent Psychoanalytic Societies (CIPS), The Gerontological Society of America, The Institute for Innovation & Implementation at UMBSSW, The Jed Foundation, The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, The Trevor Project, The Voices Project, Trust for America’s Health, United States of Care, University of Southern California, Well Being Trust.

# # #

Trust for America’s Health is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes optimal health for every person and community and makes the prevention of illness and injury a national priority. Twitter: @HealthyAmerica1

55 Organizations Call for Passage and Fast Implementation of Paid Sick Leave for all Workers as a Critical Part of COVID-19 Response

(Washington, DC) – A cross-sector group of 55 public health, health, labor, business and social policy organizations are jointly calling on the Trump Administration and Congress to pass and quickly implement a federal paid sick leave law that provides 14 days of such leave to all workers, available immediately upon declaration of a public health emergency. Fourteen days aligns with the currently recommended quarantine period for COVID-19. Furthermore, and beyond the COVID-19 response, the coalition recommends that the new law require all employers, regardless of their size, to allow workers to earn up to seven days of paid sick leave for use when they or a family member is ill or for preventative care.

The group is also proposing tax relief or interest free loans to be made available for small businesses that provide sick leave benefits during a public health emergency and that employees be allowed to take leave if schools or places of employment close due to a public health emergency. Furthermore, employees should be allowed to use leave to care for family members and should be protected from job loss or any other forms of reprisal if they comply with public health or medical advice to stay home.

Multiple health studies have found that the absence of paid sick leave has been linked to or has exacerbated infectious disease outbreaks in the past. In dealing with the current novel coronavirus, the experience of other countries indicates that aggressive social distancing measures can help slow the spread of the virus. Yet for the 34 million individuals who do not have access to paid sick leave, staying at home may not be a realistic option. Many individuals without paid sick time earn low wages, and a disproportionate percentage work in the service industry. Just 30 percent of low-wage workers in the private sector have access to paid sick leave, compared to 93 percent of higher-wage workers.

“Everyone has a role to play in managing the COVID-19 outbreak. Immediate passage and fast implementation of a national paid sick leave law will allow all workers to follow the directions of their communities’ public health officials. It is critical to mitigation efforts that people be able to stay home from work if they are sick or if they may have been exposed to the virus without facing the impossible choice of their health or their financial stability,” said John Auerbach, President and CEO of Trust for America’s Health.

A letter outlining the recommended policy actions was delivered today to Vice President Mike Pence, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, (R-KY), Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, (D-NY), House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, (D-CA), and House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA).

Organizations signing-on to the letter were:

American Lung Association

American Medical Student Association

American Public Health Association

American School Health Association

American Sexual Health Association

American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

Antibiotic Resistance Action Center, George Washington University

Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum

Association for Prevention Teaching and Research

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology

Association of Maternal & Child Health Programs

Association of Public Health Laboratories

Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health

Center for Global Health Science and Security Georgetown University

Center for Public Policy Priorities

Center for Science in the Public Interest

Children’s Environmental Health Network

Clean Habitat Inc

Colorado Association of Local Public Health Officials

Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists

de Beaumont Foundation

Florida Institute for Health Innovation

Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security

Green & Healthy Homes Initiative

Health Resources in Action

HIV Medicine Association

Immunize Nevada

Infectious Diseases Society of America

Liver Health Initiative

March of Dimes

National Association of County and City Health Officials

National Association of School Nurses

National Coalition of STD Directors

National Council of Jewish Women

National Fragile X Foundation

National Health Care for the Homeless Council

National Network of Public Health Institutes

National Organization for Women

NERDS RULE INC

NW Unangax Culture

NYU School of Global Public Health

PATH

Peggy Lillis Foundation

People’s Action

Prevention Institute

Public Health Institute

Public Health Solutions

Rollins School of Public Health

Safe States Alliance

Shriver Center on Poverty Law

Society for Public Health Education

Sumner M Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness

Trust for America’s Health

Washington State Department of Health

Washington State Public Health Association

Women’s Law Project

# # #

Trust for America’s Health is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes optimal health for every person and community and makes the prevention of illness and injury a national priority. Twitter: @healthyamerica1

TFAH Statement on COVID-19 Preparations

March 3, 2020

Now that the U.S. has transitioned from the planning phase to the response phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, the Federal Executive Branch and Congress as well as state and local governments and other stakeholders should prioritize the following:

Emergency funding is critical now, with ongoing funding to prevent future emergencies

Congress should quickly approve a supplemental funding package, with significant investments in domestic and global public health, healthcare preparedness and research and development of medical countermeasures. Federal agencies should be preparing to quickly distribute funds to states and local governments, as any delay could cost lives.

Congress and the administration should not rely on transfers between health programs to solve this problem. TFAH recommends that Congress use the supplemental funding package currently being considered to back-fill programs that have already been cut to transfer funding for the COVID-19 outbreak response. Reprogramming money from other public health initiatives, such as chronic disease prevention, won’t serve the public’s health in the long run.

The emergency supplemental funding should include the following priorities:

- Domestic public health. States and local jurisdictions have stood up their emergency operations, identifying and investigating cases, isolating and quarantining individuals, screening travelers at airports, ensuring the laboratory capacity to test patients for the virus, coordinating with the health sector to guarantee needed services are available, assessing the needs of those who are most vulnerable because of social, economic or environmental conditions and communicating with the public and healthcare facilities. Attention needs to be paid to those people who seem to be most at risk for serious health complications due to COVID-19 including the elderly and people with underlying health conditions. The breadth of the response is quickly exhausting the funding provided in annual appropriations bills.

- Healthcare response. Hospitals, health centers and other clinical facilities across the nation are preparing to identify, isolate and care for patients with COVID-19. They must do so without interrupting the routine and necessary clinical services for those with other healthcare needs. This will require training for healthcare workers on the identification of COVID-19 cases, and on appropriate infection control practices and treatment. The health care sector needs resources for some of these activities and to ensure it has appropriate personal protective equipment, necessary clinical supplies and equipment, and surge capacity.

- Medical countermeasures research and development. The U.S. government should prioritize development and procurement of COVID-19 diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments. This will require special measures to anticipate and plan to meet future need and to determine how to make appropriate services available to all with special attention to those in underserved communities.

- Global health security. The U.S. must support global efforts through the World Health Organization, USAID and other agencies to boost the capacity of lower-income countries to detect and control infectious disease outbreaks. This will protect Americans as well as other countries by decreasing the likelihood of transmission as a result of travel and commerce.

- Invest in standing reserve funds. The supplemental should fully replace funds spent from the Infectious Disease Rapid Response Reserve Fund and add a significant amount of money in this fund, so new funding can be immediately accessed if needed to fight COVID-19 and as an investment in protecting Americans from future outbreaks.

The full cost of the outbreak will become clear in the next few months, but in the short term, a significant investment is needed now. Ongoing monitoring of the course of the outbreak will determine the total amount of additional funding that may be required.

Ensure that core public health is continually funded

In addition to short-term supplemental funding, Congress must prioritize ongoing investment in public health as part of the annual appropriations process. The nation’s ability to respond to COVID-19 is rooted in our level of public health investment of the last decade. That is, being prepared starts well before the health emergency is upon us and is grounded in year-in and year-out investment in public health programs. In addition, our public health system needs a highly skilled workforce, state-of-the-art data and information systems and the policies, and plans and resources necessary to meet the routine and unexpected threats to the health and well-being of the American public. The nation has been caught in a cycle of attention when an outbreak or emergency occurs, followed by complacency and disinvestment in public health preparedness, infrastructure and workforce between emergencies. These are systems that cannot be established overnight, once an outbreak is underway.

Science is key to effective response

Science needs to govern the nation’s COVID-19 response, led by federal public health experts – including the CDC and NIH leadership – who have years of experience in responding to infectious disease outbreaks. Keeping the public fully informed is critically important, if trust is to be retained. Policy decisions – from the federal to the local level – should also be based on the best available science.

Local governments and other sectors must prepare now for various contingencies.

- Healthcare facilities must plan for a surge of patients. Such planning should include taking steps to ensure continuity of operations if a sizable number of their workforce is sick. They must prioritize the safety of patients and workers, by using personal protective equipment and by providing adequate training. Healthcare coalitions – in coordination with governmental entities – should offer situational awareness and coordination between facilities.

- Employers, including those in the healthcare sector, should adopt paid sick days protections for workers to protect the health and safety of other workers and the general public. In addition, they should assure their employees that missing work due to illness will not jeopardize their job.

- Communities that are considering school or business closures or similar measures should consider unintended consequences and take appropriate action steps. If closings are necessary authorities should assist families for whom such action is especially problematic, such as low- income families and individuals without paid sick leave, and children who rely on school meals for adequate nutrition. Homebound individuals who need access to health care personnel, equipment and medications may also need additional assistance.

The full extent of the outbreak in terms of public health, healthcare and personal costs remains to be seen. We do know that taking immediate steps to mitigate the effects of the outbreak will save lives and prevent harm.

Nuevo Informe Coloca A 25 Estados Y Distrito De Columbia En Un Nivel De Alto Rendimiento (10) en Medidas De Salud Pública Para Preparación De Emergencias

A medida que aumentan las amenazas, la evaluación anual determina que el nivel de preparación de los estados para emergencias sanitarias está mejorando en algunas áreas, pero está estancado en otras

(Washington, DC) – Veinticinco Estados y el Distrito de Columbia tuvieron un alto desempeño en una medida de tres niveles de preparación de los Estados para proteger la salud public durante una emergencia, según un nuevo informe publicado hoy por Trust for America’s Health (TFAH, por su sigla en inglés). El informe anual, Ready or Not 2020: Proteging the Public’s Health from Diseases, Disasters and Bioterrorism, encontró una mejora año tras año entre las 10 medidas de preparación para emergencias, pero también señala áreas que necesitan mejoras. El año pasado, 17 Estados se clasificaron en el nivel superior del informe.

Para 2020, 12 Estados se ubicaron en el nivel de rendimiento medio, por debajo de 20 Estados y el Distrito de Columbia en el nivel medio el año pasado, y 13 se ubicaron en el nivel de rendimiento bajo, el mismo número que el año pasado.

El informe encontró que el nivel de preparación de los estados ha mejorado en áreas claves, que incluyen fondos de salud pública, participación en coaliciones y pactos de atención médica, seguridad hospitalaria y vacunación contra la gripe. Sin embargo, otras medidas clave de seguridad de la salud, que incluyen garantizar un suministro de agua seguro y acceso a tiempo libre remunerado, está estancado o perdido.

| Nivel de Rendimiento | Estados | Numero de Estados |

| Alto | AL, CO, CT, DC, DE, IA, ID, IL, KS, MA, MD, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, NJ, NM, OK, PA, TN, UT, VA, VT, WA, W |

25 Estados y DC |

| Medio | AZ, CA, FL, GA, KY, LA, MI, MN, ND, OR, RI, TX | 12 Estados |

Bajo |

AK, AR, HI, IN, MT, NH, NV, NY, OH, SC, SD, WV, WY | 13 Estados |

El informe mide el desempeño anualmente de los Estados utilizando 10 indicadores que, en conjunto, proporcionan una lista de verificación del nivel de preparación de una jurisdicción para prevenir y responder a las amenazas a la salud de sus residentes durante una emergencia. Los indicadores son:

| Indicadores de Preparación | |||

| 1 | Gestión de incidentes: adopción del Pacto de licencia de enfermería | 6 | Seguridad del agua: Porcentaje de la población que utilizó un sistema de agua comunitario que no cumplió con todos los estándares de salud aplicables. |

| 2 | Colaboración comunitaria intersectorial: porcentaje de hospitales que participan en coaliciones de atención médica. | 7 | Resistencia laboral y control de infecciones: porcentaje de población ocupada con tiempo libre remunerado. |

| 3 | Calidad institucional: acreditación de la Junta de Acreditación de Salud Pública | 8 | Utilización de contramedidas: porcentaje de personas de 6 meses o más que recibieron una vacuna contra la gripe estacional. |

| 4 | Calidad institucional: acreditación del Programa de acreditación de gestión de emergencias. | 9 | Seguridad del paciente: porcentaje de hospitales con una clasificación de alta calidad (grado “A”) en el grado de seguridad del hospital Leapfrog. |

| 5 | Calidad institucional: tamaño del presupuesto estatal de salud pública, en comparación con el año pasado. | 10 | Vigilancia de la seguridad de la salud: el laboratorio de salud pública tiene un plan para un aumento de la capacidad de prueba de seis a ocho semanas. |

Cuatro Estados (Delaware, Pensilvania, Tennessee y Utah) pasaron del nivel de bajo rendimiento en el informe del año pasado al nivel alto en el informe de este año. Seis Estados (Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Nuevo México, Oklahoma, Vermont) y el Distrito de Columbia pasaron del nivel medio al nivel alto. Ningún Estado cayó del nivel alto al bajo, pero seis pasaron del nivel medio al bajo: Hawaii, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Carolina del Sur y Virginia Occidental.

“El creciente número de amenazas para la salud de los estadounidenses en 2019, desde inundaciones hasta incendios forestales y vapeo, demuestra la importancia crítica de un sistema de salud pública sólido. Estar preparado es a menudo la diferencia entre daños o no daños durante emergencias de salud y requiere cuatro cosas: planificación, financiamiento dedicado, cooperación interinstitucional y jurisdiccional, y una fuerza laboral calificada de salud pública “, dijo John Auerbach, presidente y CEO de Trust for America’s Health.

“Si bien el informe de este año muestra que, como nación, estamos más preparados para enfrentar emergencias de salud pública, todavía no estamos tan preparados como deberíamos estar”. Se necesita más planificación e inversión para salvar vidas”, dijo Auerbach.

El análisis de TFAH encontró que:

- La mayoría de los Estados tienen planes para expandir la capacidad de atención médica en una emergencia a través de programas como el Pacto de Licencias de Enfermería u otras coaliciones de atención médica. Treinta y dos Estados participaron en el Pacto de Licencias de Enfermeras, que permite a las enfermeras licenciadas practicar en múltiples jurisdicciones durante una emergencia. Además, el 89 por ciento de los hospitales a nivel nacional participaron en una coalición de atención médica, y 17 estados y el Distrito de Columbia tienen participación universal, lo que significa que todos los hospitales del estado (+ DC) participaron en una coalición. Además, 48 Estados y DC tenían un plan para aumentar la capacidad del laboratorio de salud pública durante una emergencia.

- La mayoría de los Estados están acreditados en las áreas de salud pública, manejo de emergencias o ambos. Dicha acreditación ayuda a garantizar que los sistemas necesarios de prevención y respuesta ante emergencias estén implementados y que cuenten con personal calificado.

- La mayoría de las personas que tienen agua de su hogar a través de un sistema de agua comunitario tenían acceso a agua segura. Según los datos de 2018, en promedio, solo el 7 por ciento de los residentes estatales obtuvieron el agua de su hogar de un sistema de agua comunitario que no cumplía con los estándares de salud aplicables, un poco más del 6 por ciento en 2017.

- Las tasas de vacunación contra la gripe estacional mejoraron, pero aún son demasiado bajas. La tasa de vacunación contra la gripe estacional entre los estadounidenses de 6 meses en adelante aumentó del 42 por ciento durante la temporada de gripe 2017-2018 al 49 por ciento durante la temporada 2018-2019, pero las tasas de vacunación todavía están muy por debajo del objetivo del 70 por ciento establecido por Healthy People 2020.

- En 2019, solo el 55 por ciento de las personas empleadas tenían acceso a tiempo libre remunerado, el mismo porcentaje que en 2018. Se ha demostrado que la ausencia de tiempo libre remunerado exacerba algunos brotes de enfermedades infecciosas. También puede evitar que las personas reciban atención preventiva.

- Solo el 30 por ciento de los hospitales, en promedio, obtuvieron las mejores calificaciones de seguridad del paciente, un poco más que el 28 por ciento en 2018. Los puntajes de seguridad hospitalaria miden el desempeño en temas tales como las tasas de infección asociadas a la atención médica, la capacidad de cuidados intensivos y una cultura general de prevención de errores. Dichas medidas son críticas para la seguridad del paciente durante los brotes de enfermedades infecciosas y también son una medida de la capacidad del hospital para funcionar bien durante una emergencia.

Otras secciones del informe describen cómo el sistema de salud pública fue fundamental para la respuesta a la crisis de vapeo, cómo las inequidades en salud ponen a algunas comunidades en mayor riesgo durante una emergencia y las necesidades de las personas con discapacidad durante una emergencia.

Se puede acceder al informe completo en Ready or Not 2020 report. |

# # #

Trust for America’s Health es una organización sin fines de lucro y no partidista que promueve la salud óptima para cada persona y comunidad y hace de la prevención de enfermedades y lesiones una prioridad nacional. www.tfah.org. Twitter: @ healthyamerica1

New Report Places 25 States and DC in High Performance Tier on 10 Public Health Emergency Preparedness Measures

As Threats Increase, Annual Assessment Finds States’ Level of Readiness for Health Emergencies is Improving in Some Areas but Stalled in Others

February 5, 2020

(Washington, DC) – Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia were high-performers on a three-tier measure of states’ preparedness to protect the public’s health during an emergency, according to a new report released today by Trust for America’s Health (TFAH). The annual report, Ready or Not 2020: Protecting the Public’s Health from Diseases, Disasters, and Bioterrorism, found year-over-year improvement among 10 emergency readiness measures, but also notes areas in need of improvement. Last year, 17 states ranked in the report’s top tier.

For 2020, 12 states placed in the middle performance tier, down from 20 states and the District of Columbia in the middle tier last year, and 13 placed in the low performance tier, the same number as last year.

The report found that states’ level of preparedness has improved in key areas, including public health funding, participation in healthcare coalitions and compacts, hospital safety, and seasonal flu vaccination. However, other key health security measures, including ensuring a safe water supply and access to paid time off, stalled or lost ground.

| Performance Tier | States | Number of States |

| High Tier | AL, CO, CT, DC, DE, IA, ID, IL, KS, MA, MD, ME, MO, MS, NC, NE, NJ, NM, OK, PA, TN, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI |

25 states and DC |

| Middle Tier | AZ, CA, FL, GA, KY, LA, MI, MN, ND, OR, RI, TX | 12 states |

| Low Tier | AK, AR, HI, IN, MT, NH, NV, NY, OH, SC, SD, WV, WY | 13 states |

The report measures states’ performance on an annual basis using 10 indicators that, taken together, provide a checklist of a jurisdiction’s level of preparedness to prevent and respond to threats to its residents’ health during an emergency. The indicators are:

| Preparedness Indicators | |||

| 1 | Incident Management: Adoption of the Nurse Licensure Compact. | 6 | Water Security: Percentage of the population who used a community water system that failed to meet all applicable health-based standards. |

| 2 | Cross-Sector Community collaboration: Percentage of hospitals participating in healthcare coalitions. | 7 | Workforce Resiliency and Infection Control: Percentage of employed population with paid time off. |

| 3 | Institutional Quality: Accreditation by the Public Health Accreditation Board. | 8 | Countermeasure Utilization: Percentage of people ages 6 months or older who received a seasonal flu vaccination. |

| 4 | Institutional Quality: Accreditation by the Emergency Management Accreditation Program. | 9 | Patient Safety: Percentage of hospitals with a top-quality ranking (“A” grade) on the Leapfrog Hospital Safety Grade. |

| 5 | Institutional Quality: Size of the state public health budget, compared with the past year. | 10 | Health Security Surveillance: The public health laboratory has a plan for a six-to eight-week surge in testing capacity. |

Four states (Delaware, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Utah) moved from the low performance tier in last year’s report to the high tier in this year’s report. Six states (Illinois, Iowa, Maine, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Vermont) and the District of Columbia moved up from the middle tier to the high tier. No state fell from the high to the low tier but six moved from the middle to the low tier. Hawaii, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

“The increasing number of threats to Americans’ health in 2019, from floods to wildfires to vaping, demonstrate the critical importance of a robust public health system. Being prepared is often the difference between harm or no harm during health emergencies and requires four things: planning, dedicated funding, interagency and jurisdictional cooperation, and a skilled public health workforce,” said John Auerbach, President and CEO of Trust for America’s Health.

“While this year’s report shows that, as a nation, we are more prepared to deal with public health emergencies, we’re still not as prepared as we should be. More planning and investment are necessary to saves lives,” Auerbach said.

TFAH’s analysis found that:

- A majority of states have plans in place to expand healthcare capacity in an emergency through programs such as the Nurse Licensure Compact or other healthcare coalitions. Thirty-two states participated in the Nurse Licensure Compact, which allows licensed nurses to practice in multiple jurisdictions during an emergency. Furthermore, 89 percent of hospitals nationally participated in a healthcare coalition, and 17 states and the District of Columbia have universal participation meaning every hospital in the state (+DC) participated in a coalition. In addition, 48 states and DC had a plan to surge public health laboratory capacity during an emergency.

- Most states are accredited in the areas of public health, emergency management, or both. Such accreditation helps ensure that necessary emergency prevention and response systems are in place and staffed by qualified personnel.

- Most people who got their household water through a community water system had access to safe water. Based on 2018 data, on average, just 7 percent of state residents got their household water from a community water system that did not meet applicable health standards, up slightly from 6 percent in 2017.

- Seasonal flu vaccination rates improved but are still too low. The seasonal flu vaccination rate among Americans ages 6 months and older rose from 42 percent during the 2017-2018 flu season to 49 percent during the 2018-2019 season, but vaccination rates are still well below the 70 percent target established by Healthy People 2020.

- In 2019, only 55 percent of employed people had access to paid time off, the same percentage as in 2018. The absence of paid time off has been shown to exacerbate some infectious disease outbreaks . It can also prevent people from getting preventive care.

- Only 30 percent of hospitals, on average, earned top patient safety grades, up slightly from 28 percent in 2018. Hospital safety scores measure performance on such issues as healthcare associated infection rates, intensive-care capacity and an overall culture of error prevention. Such measures are critical to patient safety during infectious disease outbreaks and are also a measure of a hospital’s ability to perform well during an emergency.

The report includes recommended policy actions that the federal government, states and the healthcare sector should take to improve the nation’s ability to protect the public’s health during emergencies.

Other sections of the report describe how the public health system was critical to the vaping crisis response, how health inequities put some communities at greater risk during an emergency, and the needs of people with disabilities during an emergency.

Read the full text report |