Pain in the Nation Update: While Deaths from Alcohol, Drugs, and Suicide Slowed Slightly in 2017, Rates Are Still at Historic Highs

Deaths from Synthetic Opioids Continue to Rise Sharply And Suicides Are Growing at the Fastest Pace in Years.

March 5, 2019

Executive Summary

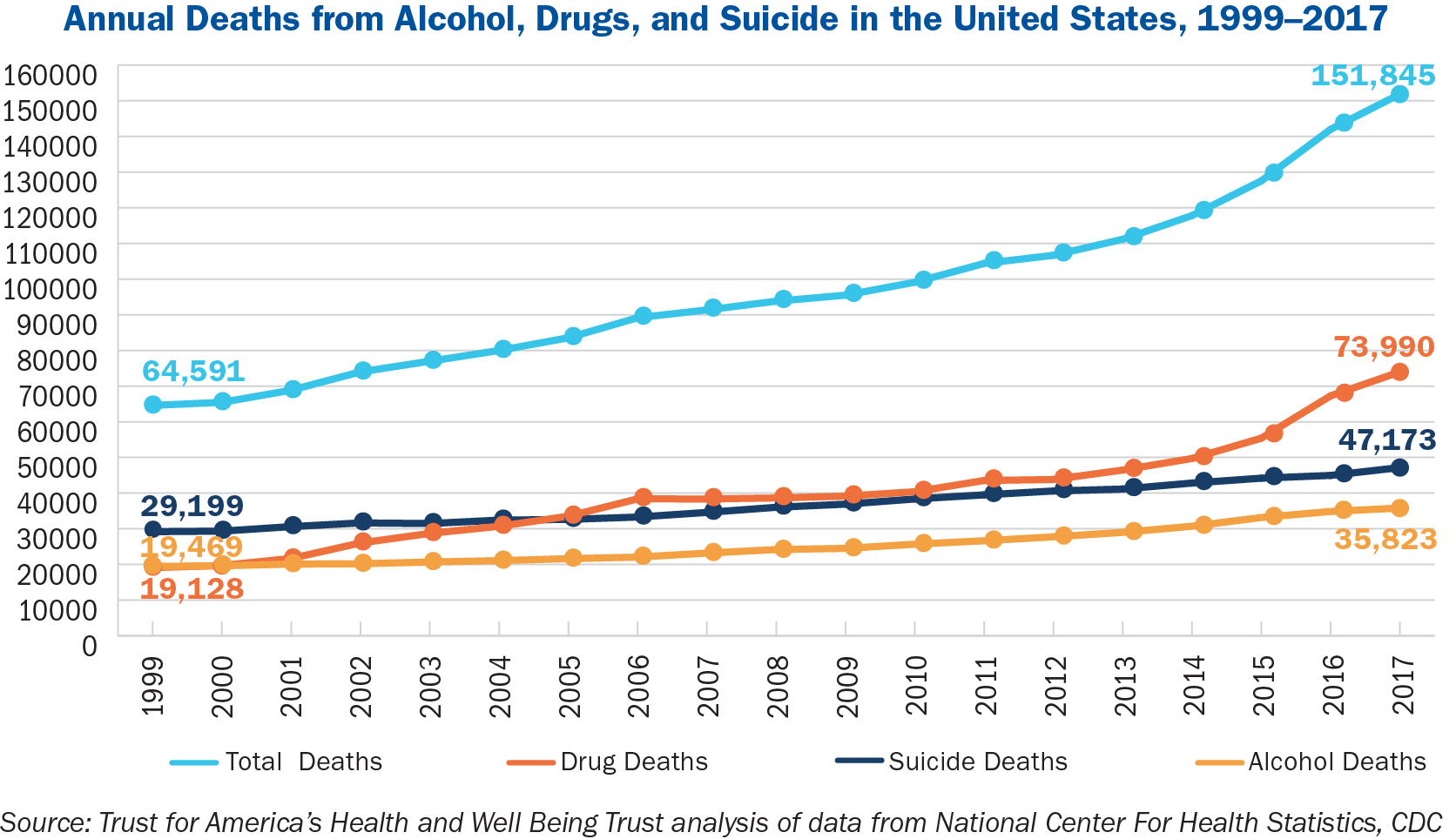

More than 150,000 Americans died from alcohol- and drug-induced causes and suicide in 2017—more than twice as many as in 1999—according to a new analysis by Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) and Well Being Trust (WBT) of mortality data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1

From 2016 to 2017, the combined death rate for alcohol, drug, and suicide increased 6 percent, from 43.9 to 46.6 deaths per 100,000 people.

While at historically high levels, the increase is lower than the prior two years, when there were 11 percent and 7 percent rises for 2015 to 2016 and 2014 to 2015, respectively.

The trends are worse for certain groups of Americans and in certain areas:

- Among those age 35-54, the rate of death by alcohol, drug, and suicide was 72.4 per 100,000, highest among all age groups.

- For all males, the rate was 68.2 deaths per 100,000. For all females it was 25.7 deaths per 100,000.

- Regionally, 91 West Virginia residents and 77 New Mexico residents per 100,000 died from alcohol, drugs, and suicide. On the low end, 31.5 Texas residents and 34.1 Mississippi residents per 100,000 died from alcohol, drugs, and suicide.

Increasing Suicide Rate

The United States also saw deaths from suicide increase more than it has since 1999, rising 4 percent between 2016 and 2017 (from 13.9 to 14.5 deaths per 100,000). Over the past decade (2008–2017), suicide rates increased 22 percent. The analysis finds that:

- The increases in deaths by suicide over the past decade (2008–2017) were driven by increases in suicides by suffocation/hanging (42 percent increase) and firearms (22 percent increase). Poisoning/overdose and other methods of suicide remained steady.

- These increases were geographically widespread but proportionally higher among younger people (particularly adolescents), Blacks, and Latinos. Absolute suicide rates remained highest among males, Whites, and those living in rural areas.

Synthetic Opioids

Synthetic-opioid deaths increased 10-fold over the prior five years, including a 45 percent climb between 2016 and 2017.2

In fact, Americans are now dying at a faster rate from overdoses involving synthetic opioids than they did from all drugs in 1999 (8.7 synthetic-opioid deaths per 100,000 in 2017 versus 6.9 drug deaths per 100,000 in 1999). In addition, the analysis found that:

- Populations dying from synthetic opioids were somewhat different from the populations affected by other types of opioids, which were more predominant in the opioid epidemic earlier in this decade. In 2017, synthetic-opioid deaths were highest among males, Blacks, Whites, adults ages 18–54, and those living in urban areas while the populations affected earlier in the decade trended comparatively more White, older, and rural.

- Synthetic-opioid deaths were concentrated in the Northeast and Midwest, while the West had relatively low rates.3

Over the past two years, TFAH and WBT have released a series of Pain in the Nation reports that track the dire consequences of America’s alcohol, drug, and suicide epidemics; share promising practices and policy solutions; and call on the nation to come together to support comprehensive prevention policies and a National Resilience Strategy to forestall future crises.

This brief, the latest in the series, covers the most recent developments in the synthetic-opioid crisis; the escalating rise in suicides; and the continued long-term climb in deaths by alcohol, drug, and suicide across demographic groups and geography based on CDC mortality data. This brief also highlights key recommendations to stem the current epidemic and avert future crises.4

Key Trends in 2017: Deaths from Synthetic Opioids and Suicide

In 2017, life expectancy decreased in the United States for the third year in a row.5 This was, in part, due to increases in death rates for alcohol, drugs, and suicide. The increases in deaths from synthetic-opioid overdoses and suicide in 2017 were particularly alarming.

Fentanyl and Synthetic Opioids

Two decades ago, fentanyl and synthetic opioids were associated with less than 10 percent of all drug deaths and resulted in fewer than 1,000 annual deaths nationwide.

In 2017, more than 1,000 Americans died from synthetic-opioid overdoses every two weeks (an average of 547 opioid overdose deaths per week), and overdoses were associated with 38 percent of all drug deaths. These increases happened almost entirely in the past few years, with mortality rates from synthetic opioids jumping in five years from less than one death per 100,000 in 2012 to 8.7 deaths per 100,000 in 2017.

These increases in synthetic opioids have touched all demographic groups and geographic areas—but not uniformly. Synthetic-opioid use was highest among males (12.8 deaths per 100,000), Blacks (8.6 deaths per 100,000), Whites (9.5 deaths per 100,000), adults ages 18–54 (15.2 deaths per 100,000), and those living in metro areas (9.2 deaths per 100,000).

This is somewhat different from the populations affected by the opioid crisis earlier in the decade, which were disproportionately White and which had a broader urban-rural spread. As of 2017, however, these deaths affected more Blacks, younger adults, and those living in metro areas.

The geographic differences in synthetic-opioid overdose deaths were even more disparate. By region, the Northeast had the highest opioid mortality rates, with 15.7 deaths per 100,000, followed by 12.1 deaths per 100,000 in the Midwest, and 8.0 per 100,000 in the South. The West, meanwhile, saw just 1.9 deaths per 100,000.

Many Western and Plains states had relatively minimal deaths from synthetic opioids in 2017. Some of this difference is likely due to the differences in heroin supply across the country and how easily it mixes with synthetic opioids: the white powder heroin that is more common on the East Coast is easy to mix while the black tar heroin more common on the West Coast is not.6,7 If the kinds of heroin available change and/or synthetic opioids became more common in those states, the number of synthetic-opioid deaths nationally could increase substantially.

Suicide

The death rate from suicide was 4 percent higher in 2017 compared with 2016, climbing from 13.9 to 14.5 deaths per 100,000. This is the largest annual increase recorded since at least 1999 (when the dataset begins). Over the past decade (2008–2017), suicide rates increased 22 percent.

The rising suicide rates over the last decade (2008–2017) were largely due to more suffocation/hanging suicides and firearm suicides. Suffocation/hanging suicides rose 42 percent, from 2.8 to 4.0 deaths per 100,000, and firearm suicides rose 22 percent, from 6.0 to 7.3 deaths per 100,000. Other methods of suicide, including overdose/poisoning, have held steady over the same time period (remaining between 3.0 and 3.2 deaths per 100,000).8

Notably, the methods of suicide that rose also accounted for the majority of suicides: firearm suicides were 51 percent of and suffocation/hanging suicides were 28 percent of total suicides—and both are particularly lethal methods (firearm suicides prove lethal more than 80 percent of the time, and suffocation/hanging suicides are lethal more than 60 percent of the time, compared with less than 2 percent for drug overdoses/poisoning and cutting).9

Over the past decade (2008–2017), suicide increased in nearly every state (except Delaware and the District of Columbia) and touched every region of the country. There were substantial variations by demographics however—with larger proportional increases among younger people and racial and ethnic minorities, and continued higher rates and absolute increases among males, Whites, and those living in rural areas.

In particular, one of the most disturbing trends of the last decade is the rise in deaths by suicide among children and adolescents (although the number and rate is still relatively low compared with adults). Between 2016 and 2017, suicide death rates among children and adolescents ages 0–17 increased by 16 percent (from 2.1 to 2.4 deaths per 100,000).

Suicide rates among young adults ages 18–34 increased 7 percent (15.9 to 17.0 deaths per 100,000), and rates increased 2 percent for adults ages 35 and older.

This same pattern held over the last decade (2008–2017): suicide among children and adolescents increased 82 percent (from 1.3 to 2.4 deaths per 100,000), young adults increased 36 percent (12.5 to 17.0 deaths per 100,000), and adults ages 35 and older increased 12 percent (16.4 to 18.4 deaths per 100,000).10 Over that same decade, 12,660 youth under age 18 died from suicide.

Suicide rates also increased proportionally more among racial and ethnic minority groups, particularly among Blacks and Latinos (while still remaining substantially lower than White suicide rates). Suicide rates among Blacks increased 9 percent last year (from 6.1 to 6.7 deaths per 100,000) and 30 percent over the last decade (5.1 to 6.7 deaths per 100,000), and rates among Latinos increased 5 percent last year (6.4 to 6.7 deaths per 100,000) and 36 percent over the last decade (4.9 to 6.7 deaths per 100,000).

For suicide death rates by additional demographic and geographic breakdowns, see the chart on page 8 of the full report.

Endnotes:

1. All mortality data in the brief is from the National Center for Health Statistics at CDC, and was obtained from the WONDER database in December 2018. For more information on method, see appendix on page 18.

2. Methadone is grouped separately and is not included in the synthetic-opioids category in this brief.

3. As defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, the Northeast includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont; the Midwest includes Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin; the South includes Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, South Carolina, and Virginia; and the West includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

4. Segal L, et al. “Pain in the Nation: The Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Crises and Need for a National Resilience Strategy”, Trust for America’s Health & Well Being Trust, November 2017. https://www.tfah.org/report-details/pain-in-the-nation/

5. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, and Arias E. “Mortality in the United States, 2017.” National Center for Health Statistics, NCHS Data Brief, no. 328, November 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db328.htm (accessed January 10, 2019).

6. Frenk RG, Pollack HA. “Addressing the Fentanyl Threat to Public Health”, New England Journal of Medicine, February 2017; 376:605-607; https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1615145

7. Chang A, Macy B. “What’s Behind The Geographical Disparities Of Drug Overdoses In The US.” National Public Radio, November 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/11/29/671996727/whats-behind-the-geographical-disparities-of-drug-overdoses-in-the-u-s

8. Research suggests that suicide by drug overdose may be undercounted due to the difficulty of understanding intent, which means the overall suicide rate is higher than official reports and the true rates and trends of overdose/poisoning suicides need more careful study.

See: Rockett IRH, Caine ED, et al. “Discerning Suicide in Drug Intoxication Deaths: Paucity and Primacy of Suicide Notes and Psychiatric History.” PLoS ONE, 13(1): e0190200, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190200 (accessed January 10, 2019).

9. Spicer RS and Miller TR. “Suicide Acts in 8 States: Incidence and Case Fatality Rates by Demographics and Method.” American Journal of Public Health, 90(12): 1885, 2000. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/means-matter/means-matter/case-fatality (accessed January 10, 2019).

10. Suicide is not an official cause of death for children under age 5.

# # #

Trust for America’s Health is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that promotes optimal health for every person and community and makes the prevention of illness and injury a national priority.